The Masonic Genius of Robert Burns

Source: Ars Quatuor Coronatum, Vol. 5, 1892, p. 46-53,

LODGE QUATUOR CORONATI, NO. 2076, LONDON.

Friday, 4th March, 1892.

The Masonic Genius of Robert Burns

by Bro. Benjamin Ward Richardson,

M.D., L.L.D., F.R.S., F.S.A.

Worshipful Master and Brethren,

When I speak of the Masonic genius of Robert Burns, I mean that his genius, which is universally admitted, partakes of the genius of Masonic order or type. In this discourse I shall consider him first from this point of view.

Next, I shall speak of his poetic genius as appealing primarily to the Masonic brotherhood, and as fostered and fed by that fraternity. I shall then proceed to treat of his love for the brotherhood as manifested in the productions of his poetic genius. Finally, I shall for a few moments dwell on the tendency and tenure of his work as Masonic in quality in the higher and nobler, shall I not say the highest and noblest, forms of Masonic liberty and moral amplitude. This will divide my subject into four sections or parts, and will enable brethren who may join in the discussion to fix on particular points as they follow what I shall venture to lay before them.

In studying the first section of this division – the genius of Masonry in relation to the natural genius of the man – we must know the man from the &st, know him from his own heart. In an order or fraternity like Masonry there is a true, a deep, and subtle genins which holds it together; and that the order may be held together there must be, in a greater or lesser degree, the same kind of genius in every individual member. All fraternities of might and effect and endurance, whether they be considered good or bad by outsiders, must be constructed on this plan. Orders, in fact, are composed of men born to aptitudes befitting the order. There are, of course, exceptions to this general rule. There are in every fraternity members who are perfectly indifferent; there are members who are merely converts; and there are, in all great combinations, a few who may even be inimical. But on the whole the strongest societies have for their centre an overwhelming unity, at the head of which are they who are particularly bound to the principles that are at stake, and who come into the mastery of those principles by what is naturally a common bond. In this position Robert Burns stands as regards the Masonic bond and unity. Masonry, when he found it, was akin to his native genius; it was to him that touch of nature which makes all akin.

For the birth of this sympathy we have to turn to the best picture we can get of the poet while his nature was being moulded into the form it took as Mason and poet. Fortunately for us, owing to the interposition of a very remarkable man, who is now too much forgotten, we have an account of this period of the poet’s life from the poet himself. The scholar who obtained this treasure was Dr. John Moore, the father of that illustrious Sir John Moore, hero of Corunna, on whom Wolfe wrote the immortal poem beginning,-

«Not a drum was heard nor a funeral note,

As his corse to the ranqarts we hurried,

Not a soldier discharged a, farewell shot

O’er the grave where our hero we buried.»

Dr. Moore, whose life I have recently written, and of whom I present three portraits for your inspection, was by profession a physician, residing first in Glasgow and finally in London; but he added to his Esculapian gifts those of the traveller, the man of the world, and the industrious writer. He was in France with the Duke of Hamilton before the days of the great Revolution, and with the same clearness of foresight as his friend Smollett, predicted the great event that must follow from what he beheld in progress. Again, he was in Paris in the early days of the great Revolution itself; heard the fist shots fired at the Tuilleries�; attended the meetings of the National Assembly�; and left the finest description of Marat, whom he knew personally, that has ever been written on that famous infamous person. His journal of the days of the Revolution has been more cribbed from, without acknowledgment, than most works of original men. But he was more than the jonrndist of striking events�; he was himself an artist in letters,aud his story » Zelucco » was the inspiration of the poem » Childe Harold,» which Byron Left to the admiring world. Still further, Dr. Moore was of biographic taste, and was anxious, on all suitable occasions, to get from their prime sources the histories of remarkable men. Thus it was he got from Robert Bnrns himself that account of his, Burns’, early days with which, I doubt not, most of you are familiar. Gilbert Burns, brother of the poet, says that in this narrative the poet set off some of his early companions «in too consequential a manner,» which is perhaps too tme, for poets are apt to be poets all over, in prose as in verse�; anyway, there is rendered in this composition the fact which chiefly concerns us. that companionship of the brotherly type was the early love of the after Mason. Burns rejoiced in all social gatherings, and cared nothingwhatever for his daily work when he was encircled, in the evening of the day, with his friends whom, in love or in war, in song or in story, he impetuously led. He waa mystic from the first, and breathed poetry before he knew it himself. Like Pope�:-

He was living at Tarbolton with his family when these faculties, belonging to his seventeenth year, developed themselves. He possessed, he says, a curiosity, zeal, and intrepid dexterity that recommended him as a proper second, and he felt as much pleasure in being in the secret of half the loves of Tarbolton as ever did statesman in knowing the intrigues of half the courts of Europe. He felt that to the sons and daughters of poverty, «the ardent hope, the stolen interview, the tender farewell, are the greatest and most delicious parts of their enjoyments.» This was a glance at the loves of the simple�: he found it to apply, later on, to other mysteries, and in all bases his heart beat sympathetically to the sentiment.

In his nineteenth year he made a change in his life which is curious, symbolically, and perhaps had relation to after Masonic work of the speculative rather than the working character. He spent his nineteenth summer on a smuggling coast, a good distance from home, at a noted school, to learn mensuration, surveying, and dialling. Here, although he took part in scenes which had better have been avoided, he went on » with a high hand » at his geometry, «hill the sun entered Virgo, which was always a carnival in his boaom,» and then in a few weeks he left his school to return home. But he had considerably improved, and from his studies had certainly learned the use of the tools of a Mason, the rule, the Compass, the level, and the skerritt.

All this was congenial towards Masonry in its form of speculative mystery, and we need not, therefore, be surprised that it was not long before he joined our ancient order. There was, at the time of his residence at Tarbolton, a Masonic Lodge called St. Dltvid’a. The harmony which ought to exist in all Lodges of the Craft does not seem to have been perfect in this one. There had been another Lodge in Tarbolton, known as the St. James’, and some discordant elements might have come down from that Lodge to the St. David’s, which, for a time, superseded it. Be that as it may, St. David’s had the honour of receiving the young Scottish poet into its bosom. Burns was initiated in St. David’s Lodge, Tarbolton, on July 4th, 1781, he being then in his twenty-third year. He became from that moment one of the most devoted of Masons. In every way Masonry was congenial to his mind. There was in it a spirit of poetry which was all the sweeter to him because it was concealed, and there was in it the fact of something done which the best in the world copied from without knowing the source of the inspiration�; something like that which Shelley afterwards, unconsciously as applied to this subject, expressed in the exquisite song to the skylark:-

«Like a poet hidden

In the light of thought,

Singing hymns unbidden

Till the world is wrought

To sympathy with hopes

And fearn it heeded not.»

and which Burns himelf, in another form and measure, expressed in the lines:-

«The social, friendly, honest man,

Whate’er he be,

‘Tis he fulfils great Nature’s plan,

And none but he.»

Burns had no sooner been, initiated into Masonry than be threw himself into work oonnected with it with his whole heart. He found, nevertheless, that even among Masons there may be discord. The old feud in the St. David’s Lodge increased, and came, at last, to such a pitch, that a sharp division took place. In the year 1782 a number of the members of the Lodge seceded, and re-formed the old and almost forgotten St. James’ Lodge of Tarbolton. Burns was amongst the seceders, and the newly-formed Lodge was destined, largely by his warm adhesion to it, to become one of the most famous historical Lodges Scottish Masonry ever boasted of. In this Lodge the poet found poetry, and in it, above all other prizes in the world, he found friendship. This fact leads me, naturally, to the second division of my paper: the fostering care he experienced as a poet from Masonic communion and enthusiasm.

By the time Burns joined the Lodge at Tarbolton he was a poet. He was not a poet of any wide renown, but he had written poems which some of his immediate circle of friends admired. His life up to this period, had been one of great strain and poverty. Born in a little cottage near Alloway Kirk, on the Doon, in Ayrshire, he had moved with his parenta, when about seven years of age, to a farm in the parish of Ayr, called Mount-Oliphant. The farm w:s a ruinous affair. Here he worked on the land as a farm-boy fortwelve years, after which the family passed, with no better fortune, to another farm, called Lochlea, in the parish of Tarbolton. Robert worked like the rest on this farm, but he ww not exclnsively engaged on farm labour. He went, as already told, to a sea coast place, Kirk Oswald, where he learned mensuration and other parts of arithmetic, which ultimately fitted him for the duties of an excise officer, and on the whole he picked up, at Kirk Oswald parish school, much information that served him well, with some tricks which did not serve him so well. He returned to the farm at Lochlea in his twentieth year�; resumed work with his brother Gilbert, fell in love with a servant-maid, who jilted him, and led rather a wild life altogether. He and his brother tried their hands at flax-farming at the neighbouring village of Irvine, but during a New Year’s day carousal the flax shop took fire and the whole stock was burnt up. Worse still, he got into bad company and into some disrepute.

Affairs at Lochlea went wrong with the excellent father of the poet, and in February, 1784, that good man died. The loss of his father incited the poet to a better life, and he and his brother took a larger farm at a place called Mossgiel, in the parish of Mauchline, near Tarbolton. The farming project failed, and good resolutions failed with it.

Our Brother the poet Burness, for he assumed the shorter name of Burns later on, was not at the moment of his career at which we have arrived, in a very happy or a very hopeful condition. He was poverty stricken, he was reckless, he had sent into the world an illegitimate child, and be was looked upon askance by those friends about him, who considered good morals tbe fist of acquirements. Yet, with it all, he was not the absoluterake or prodigal which many have depicted him. He had availed himself of what advantages had come before him. He had been for a short time blessed by the instruction of a tutor named Murdock, from whom he had learned among other things French, in which language he greatly delighted, and he had gathered together vruions classical and romantic books which he read with the avidity a nature such as his alone experiences. He had seen a little of the world at Kirk Oswald, and he had acquired some knowledge of the exact sciences. But above all, he was a poet and a Mason.

Opinions have differed since his death, as they differed in his own time and amongst his own friends, on the point whether he did ill or well in joining the Lodge in Tarbolton. Masonry was rather popular in Scotland, but many thought that Robert Burness had joined it, not because of the goodness there was in it, but became of

and in this view there was much sense for sober going people, since it cannot be denied that, Scotia’s drink was freely floated in the Lodges, when refreshment followed the serious business of labour. Moreover, Robert himself, at his twenty-third year, was a sufficient cause for alarm amongst his friends. He was, physically, not well. He had frequent dull headaches, and he was laying the seeds for those conditions of faintness and palpitation of the heart, which as his brother Gilbert tells us, were the bodily burthens of after years.

He was, moreover, at this time, exceedingly unbridled in his tastes. He was the prime spirit of a bachelor’s club, which, althongh the expenses were limited to threepence per bachelor each night, was an assembly that did not particularly raise him in public estimation; and he was always in love, not with one object of affection, but with any and many, according to fancy, investing, by his fancy, as Brother Gilbert informs us, each of his loves with such a stock of charms, all drawn from the plentiful stores of his imagination, that there was often a great dissimilitude between the fair captivator as she appeared to others and as she seemed when bedecked with the attributes he gave to her. Up to this time he was not given to intoxication, and when, with his brother and family he entered into partnership for the farm of Mossgiel, he contributed his share of expenses, and lived most frugally. He had written songs and other poetical pieces, which pleased those who surrounded him, and the poems had accumulated to a goodly number, but they were buried in necessity, and it is very doubtful if by his own efforts they would everhave been brought to light.

Day by day his adversity grew more and more pressing. At last a crisis. Amongst his many loves there was one who held to him to the end the most firmly, namely, Jean Armour, and with her love went so far it could no longer be concealed. In the strait the lovers came to a determination. They entered into a legal acknowledgment of «an irregular private marriage,» and it was proposed that Burns should at once proceed to Jamaica as an assistant overseer on the estate of Dr. Douglas. Strangely, the parents of Jean Armour objected to the acceptance of the marriage, under the impression that great as had been the folly of Jean she might live to do better than tie herself for life to a scapegrace. To Burns this slight was intolerable, although in a kind of contrition he seemed to bend to it. It settled his resolve, he would go to Jamaica, and by honest work would make up for past misfortune.

It happened that much time was required before he could make a start for his new sphere of labour, and, meanwhile, as preparations were going on something else occurred, on which, as on a pivot, the fate and fame of Robert Bnrns turned. In the Lodge of St. James, Tarbolton, there was an important member, a writer to the signet, living, near by, at Mauchline, and the landlord of the farm of Mossgiel. This was Gavin Hamilton, a happy-go-lucky, warm-hearted, merry fellow, much attached to the ploughman poet, some of whose effisions he had heard in song at least, and towards whom he entertained a sincere admiration. Hamilton suggested that Burns should collect and publish an edition of his poems, and that the expense should be met by a subscription. The plan was after the poet’s own desire, I may say fervent desire. He longed to leave his name to posterity, and, in fact, cared for little else. The ordinary life was to him already a burden, but the idea of immortal fame was something worth living for, and was even worth the weariness of the world. He seized, therefore, on the proposal with avidity. It was early in the year of 1786, and his vessel for Jamaica would not sail until November; let then the proposal, of all things, be carried out.

With all his faults Burns stood high in his Lodge of St. James, at Tarbolton. In 1784 he was made Depute Master, Major General Montgomery being Worshipful Master. In 1785 he attended Lodge nine times, and acted many times, if not every time, as Master. In 1786 he attended nine times, and at the second meeting, held on March the first, passed and raised his brother Gilbert. How well he fulfilled the duties of his office is told by no less a person than the famous metaphysical scholar, Dugald Stewart, who had a neighbouring country residence at Catrine. Stewart specially commends the ready wit, happy conception and fluent speech of the Depute Master of St. James’ Lodge. There can be no doubt that the Lodge, in return, became responsible altogether for the issue of the first volume of poems of Robert Burns, not as an official act, but as an act of personal friendship for their talented brother�; and, under their initiative, he went to Kilmarnock, in order to see through the Press the new and now precious first edition of poems dated April 16th, 1786. Whilst residing in Kilmamock, he met with the warmest reception and encouragement from the Masonic brethren there. He became a visitor of their St. John’s Lodge at once, and on the 26th of October, 1786, was admitted an honorary member. The brethren of this Lodge agsisted him also substantially in his venture. Brother Major Parker subscribed to thirty-five copies of the book, and Robert Muir, another of the brethren of St. John’s, to seventy-five copies, whilst a third brother, John Wilson, print,ed and published the volume. In short, the first edition was in every sense such a Masonic edition, we may almost declare that but for Masonry the poems of Robert Burns, now disseminated over all the world, had merely been delivered to the winds as the mental meanderings of a vulgar and disreputable Scottish boor. Thus, the genius of Masonry discovered and led forth the genius of one of the greatest of the poets of Scotland.

The good genius of masonry did not end at this point. It brought out the volume of poems, and made the author master of a little balance of money for his work�; but, alas, the return was not sufficient to prevent the evil fate that would separate him from all he loved best. He was still pursued by ill fortune. His little bit of luggage was on its way Greenock, he following it, playing at hide-and-seek, and wishing Jamaica at the bottom of the sea, when a letter reached him again from a brother mason, a gentle blind brother, with a taste for the muses, Brother Dr. Blacklock, suggesting that a new edition of the Kilmmnock poems should be published in Edinburgh, and that their author should go to that fair city and superintend the undertaking. Burns at once responded, and on the 26th of November, instead of being on the sea for the West Indies, he was in the modern Athens, and in the midst of enthusiastic friends, a11 warmed to friendship by the mystical fire. Here things went grandly. Henry Mackenzie, a good mason and good writer, author of «The Man of Feeling,» announced through a paper, called the Lounger, that a new poet had been born to Scotland; and David Ramsay, editor of the Evening Courant, another brother, represented him to his world of letters as�:-

And so this Prince of Poets ploughed his way into the best circles of Auld Reekie. He was at once great in the Masonic Lodges. The Worshipful Grand Master Charteris, at the Lodge of St.Andrews’, proposed as a toast, «Caledonia and Caledonia’s Bard Brother Burns,» «a toast,» the Bard writes «which rang through the whole assembly, with multiplied honours and repeated acclamations; while he, having no idea such a thing would happen, «was downright thunderstruck, and trembling in every nerve» made the best return in his power. Jamaica vanished�!

Early next year, February 1st, 1787, the Edinburgh edition of the poems, being well in hand, Burns was admitted by unanimous consent, a brother of the Canongate Kilwinning Lodge, in which on the first of the following month the Master – Fergussen of Craigdarrock – dignified him as Poet Laureate of the brotherhood, and assigned him a special poet’s throne. The time now quickly arrived, April 21st, for the appearance of the new volume. The members of the Caledonian Hunt, under the leadership of Lord Glencairn, to whom the poet was introduced by Brother Dalrymple, subscribed liberally, and altogether a subscription list of 2,000 copies was secured, the Masonic influence again leading the way. «Surely,» says an anonymous writer on this subject, » a son of the Rock,» as he styled himself, but whom I have since found to have been Mr. James Gibson, of Liverpool, and not himself a Mason, » surely never book came out of a more Masonic laboratory. Publisher, printer, portrait painter, and engraver of the portrait were a rare class of men – all characters in their way – and all Masons.» Creech was the publisher, Smellie was the printer, Alexander Nasmyth was the painter, and Bengo was the engraver, each and all Masons of the staunchest quality. Under such support the poems were bound to go, and they went, carrying their author with them into the glory he most desired.

As it is not my business to dwell on the life of Burns out of its Masonic encircling, I need not to dwell on his later career�; his flirtations with Clarinda, his love with Mary Campbell; his journeyings and jollifications�; his melancholy and his remorse�; his marriage with Jane Armour�; his failure as a farmer at Ellislaud�; his entrance into the excise; his residence at Dumfries�; his final intemperance and his early death on July 21st, 1796. Let it be sufficient to add that St. Abbs’ Lodge at Lyemouth made him a Royal Arch Mason, omitting his fees and considering themselves honoured by having a man of such shining abilities as one of their companions�; that when he settled in Dumfries, the Lodge of St. Andrew received him with open arms�; and that to him ever, to use the words of Mr. Gibson, «Masonry held out an irresistible hand of friendship.»

I come now to the third point to which, Worshipful Master, I would direct the mind of the Lodge – the love of the poet for the brotherhood, as represented in his poetical works.

There are at least eight poems in which Masonry is directly connected with the theme of the poem or song. A short epistle in verse to Brother Dr. Mackenzie, informing him that St. James’ Lodge will meet on St. John’s day, is racy and refers to a controversy on morals which had been going on in the little circle. An elegy to Tam Samson relates to a famous seedsman, sportsman, and curler, but above all a Mason of the Kilmarnock Lodge, and a sterling friend of all who knew him in friendship’s mysteries.

«The brethren o’ the mystic level

May hing their heads in waefn’ bevel,

While by their nose the tears will revel

Like ony bead.

Death’s gien the Lodge an unco’ devel,

Tam Samson’s dead.»

In like manner, but with a tender sweetness and more subdued verse, he writes another elegy on one to whom he was bound by the mystic tie, Sir James Hunter Blair. The poem is finely conceived. The poet supposes himself wandering in some secluded haunt�:-

«The lamp of day, with ill-presaging glare,

Dim, cloudy, sinks beneath the western wave,

Th’ inconstant blast howls through the darkening air,

And hollow, whistles in the rocky cave.»

The moon then rises «in the livid east,» and among the cliffs the stately form of Caledonia appears» drooped in pensive woe.» «The lightning of her eyes» is imbued in tears�; her spear is reversed�; her banner at her feet. So attuned she sings her sorrow for the loss of her son and the grief of her sons, not omitting the sons of light and science:

«A weeping conntry joins a widow’s tear,

The helpless poor mix with the orphan’s cry�;

The drooping arts surround their patron’s bier,

And grateful science heaves the heartfelt sigh.»

In an epistle to his publisher, William Creech, whose Masonic virtues I have already noted, we get just a glimpse into Kilwinning Lodge, Edinburgh, when Willie, that is Creech, is on his travels in London. » Willie’s awa’.»

«Now worthy Gregory’s latin face,

Tytler’s and Greenfield’s modest grace,

Mackenzie, Steward, sic a brace,

They a’ maun meet some ither place.

Willie’s awa’�!

Gregory of the Latin face was the famous Dr. James Gregory, perhaps the purest Latin writer medicine ever produced in his country, but better known as the inventor of the most nauseous, and yet one of the most useful medicines – Gregory’s powder. Greedeld was the eminent Professor of Rhetoric�; and Stewart the illustrious Dugald.

«Willie brew’d a peck of meut» is a Masonic song of genius. Willie was Brother William Nicol, of the High School, Edinburgh, with whom the poet made a tour to the Highlands�; Allan was Brother Allan Masterton, and Rob was Brother the Poet himself; three Masons holding an informal Lodge at Nicol’s place at Moffat during the summer vacation. It was such a joyous meeting that each in his own way celebrated it�; Willie -Nicol- with the maut, Rob -Burns- with the song, and Allan -Masterton- with the music.

The poem of Death and Dr. Hornbook is of Masonic origin. Hornbook was Brother Wilson, schoolmaster of Tarbolton, and a member of the Lodge, whotook to reading medical books and dabbling in physic. One night, after going from labour to refreshment, Wilson paraded his medical knowledge and skill too loudly to miss the watchful Robert, and Robert, on his way home, was accompanied by this mixture of pedantry and pbysic to a certain point, where they shook hands and parted. Left alone, the old fancies of goblins and spirits came on the poet; Death came, and after a conversation with that reaper, the flowing satire on the poor dominie was composed. These circumstances, Gilbert Burns says, h& brother related as he repeated the verses to him the next afternoon, while Gilbert was holding the plough and Robert was letting the water off the field beside him. How the poem took when it was first published is matter of history. It settled poor Brother Wilson for good as a selfconstituted doctor at Tarbolton, the verse beginning with the words, «A bonnie lass ye kenn’d her name,» telling with potent effect.

Wilson, I believe, was the only Mason Burns lampooned, and he without enmity. Wilson, however, had to leave Tarbolton, and, retreating to Glasgow, became clerk of the Gorhals parish, and lived until 1839, half-a-century after the Tarbolton exodus. Cromek, one of the writers on Burns1, who knew Wilson in his later days, says Wilson had so little pedantry about him that a man who never read the poem would scarcely discover any, and I have heard others who also knew him make the same observation.

The song entitled » The sons of old Killie,» beginning-

» Ye sons of old Killie assembled by Willie

To follow the noble vocation,

Your thrifty old mother has scarce such another

To sit in that hononred station.

I’ve little to say, but only to pray,

As praying’s the ton of your fashion�;

A prayer from the muse you well may excuse,

‘Tis seldom her favourite passion.»

was produced at a festival of the Kilmarnock Lodge, Willie aforesaid being Brother William Parker, the Worshipful Master.

- 1 Cromek, a Yorkshireman, an art publisher, engraver, and in some sense, an artist, went to Scotland, ten years after the poet’s death, to collect materials for a volume on Burns, as a kind of supplement to four volumes that had already been written by Dr. Currie. The volume was entitled the » Reliques of Bourns,» and was published by Cadell and Davies in 1808.

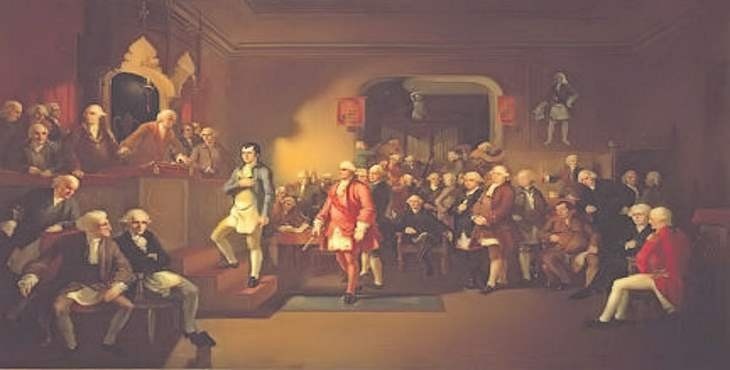

I must not weary you with too many of these snatches of Maaonic light from our immortal brother, but it would be impossible to omit the one jewel of jewels of song which he sang, or rather chanted than song, to the tune of » Good night, and joy be wi’ you a’,» at the meeting of St. James’ Lodge, Tarbolton, at the moment when his little box of luggage was on its way to Greenock, and he, very soon as he believed, was bound to follow it. We can picture to ourselves the Lodge, Major-General James Montgomely, W.M., in the chair; the Wardens in place�; the brethren round the board, and the Depute Master, heart-broken, thinking it the last song he shall ever compose in dear old Scotland. We may picture the meeting, but the emotion of that moment can be but a faint expression.

«Adieu�! a heart-warm fond adieu!

Dear brothers of the mystic tie!

Ye favour’d, ye enlighten’d few,

Companions of my social joy.

Though I to foreign lands must hie,

Pursuing fortune’s slidd’ry ba’.

With melting heart, and brimful eye,

I’ll mind you still, though far awa’.

Oft have I met your social baud,

And spent the cheerful festive night,

Oft, honoured with supreme command,

Presided o’er the sons of light,

And by that heiroglyphic bright,

Which none but craftsmen ever saw�!

Strong memory on my heart shall write,

Those happy scenes when far awa’�!

May freedom, harmony, and love,

Unite you in the grand design,

Beneath the omniscient eye above,

The glorious Architect divine�!

That you may keep the unerring line,

Still rising by the plummet’s law,

Till order bright completely shine

Shall be my prayer when far awa’.

And you farewell�! whose merits claim

Justly that highest badge to wear.

Heaven bless your honoured noble name

To Masonry and Scotia dear.

A last request permit me here,

When yearly ye assemble a’,

One round – I ask it with a tear-

To him, the Bard, that’s far awe’.»

The tear was quenched; in pursuing «fortune’s slidd’ry ba» the poet was led to Edina instead of Jamaica; yet even this not without one sorrow, one tear�; for on the very day he entered the beautiful city to be for a flicker her hero of ploughmen, William Wallace, Grand Master of Scotland, «To Masonry and Scotia dear,» ascended to the Grand Lodge above.

I pass to the last fragment of my discourse, namely, the tendency and tenure of the genius of Robert Burns as a Masonic poet. With the deepest admiration for a poet whose words have been familiar to me and whose sentiments have touched my heart from the earliest days of my recollection, I am not blind to his sins of emotion. I know his faults. But in all the poet said, and, I believe, thought, about the principles of Masonry, he kept by the unerring line, as if indeed the eye omniscient were upon him�; and as if in pure Masonry, in its tenets, it symbolisms, and, in the best sense, its practices, there is a secret spell on the mind and heart, in which the mind and heart must live and move and have its being.

The best idea of Masonry on these foundations found its noblest utterance, from our poet brother, in his peroration to St. John’s Lodge, Kilmamock.

«Ye powers who preside o’er the wind and the tide,

Who marked out each element’s border�;

Who founded this frame with beneficent aim,

Whose sovereign statute is order.

Within this dear mansion may wayward contention

Or withering envy ne’er enter�;

May secrecy round be the mystical bound,

And brotherly love be the centre.»

Worshipful Sir, let that peroration be mine to-night, to Quatuor Coronati.

Deja una respuesta